I examine the complex interplay between children’s linguistic, mathematical, and problem-solving skills.

My research challenges common assumptions about how we measure children's academic abilities, particularly for students who speak multiple language varieties. Rather than viewing linguistic diversity as a barrier to learning, I investigate how children's rich language skills represent sophisticated cognitive abilities that should be recognized and valued in educational settings. Through a combination of rigorous empirical research and innovative assessment design, my work demonstrates that traditional academic assessments often create unfair disadvantages for linguistically diverse children—not because these children lack ability, but because the assessments fail to align with their lived experiences and language strengths. By centering children's own voices and mathematical experiences, I work toward developing more equitable approaches to educational measurement that reveal rather than mask all children's true competence. This research program bridges cognitive science, educational assessment, and social justice to create meaningful change in how we understand and measure academic achievement.

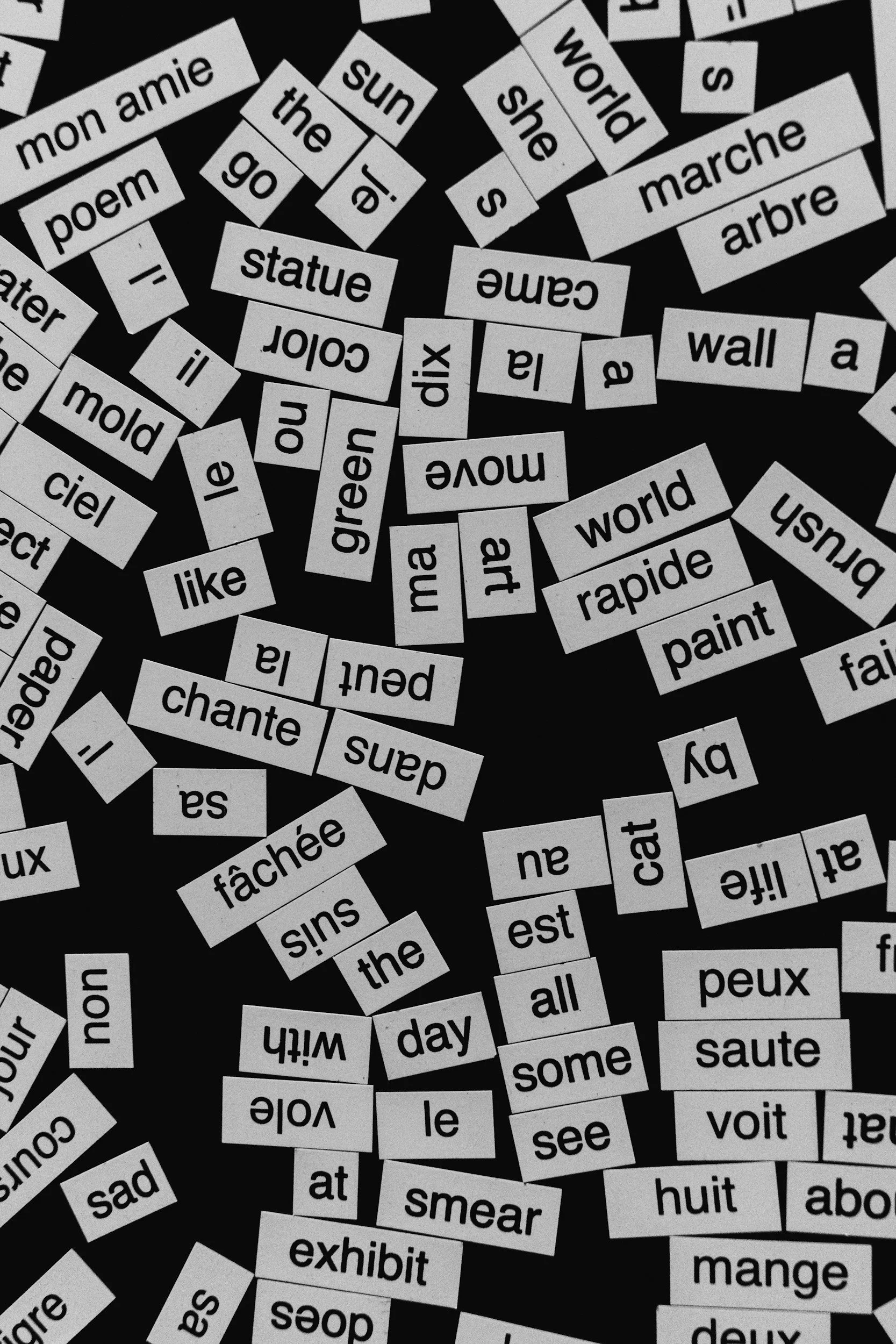

Managing the rules of two, sometimes conflicting, language systems is a complex problem-solving endeavor

Many children are skilled users of multiple language varieties, seamlessly navigating between the language system they use at home and the general American English expected in school settings and on formal assessments. Speaking both African American English dialect (AAE) and general American English isn't simply about "switching" between two systems—it requires sophisticated mental flexibility and problem-solving skills. My ongoing research examines how children navigate different grammatical rules and language expectations across contexts, treating this linguistic skill as a form of cognitive competence rather than a deficit. This work helps us understand that when children manage multiple language systems, they're engaging in complex thinking that should be recognized and valued in educational settings. By better understanding these linguistic problem-solving abilities, we can design more equitable approaches to assessment and learning that build on rather than penalize children's diverse language strengths.

Language influences children’s patterns of errors on math problems

Considering children’s language profiles is particularly important for interpreting their performances on academic assessments. When children solve math word problems, we typically assume that any mistakes they make reflect gaps in their mathematical understanding. My published research challenges this assumption by showing that the language used in these problems can create barriers that have nothing to do with math skills. Working with African American children who speak AAE, I found that children were nearly six times more likely to struggle with word problems compared to the same math presented as numbers only. The key finding: children who used more AAE dialect features had significantly more difficulty selecting appropriate strategies to solve word problems, even when the problems were read aloud to remove reading barriers. This demonstrates how linguistic mismatches can mask children's true mathematical abilities and create unfair disadvantages in testing situations.

Math word problems are designed to measure real-world problem-solving… but whose real-world do they represent?

My research about language barriers raises fundamental questions about the design of our assessments: do current math problems actually reflect the mathematical experiences that different children have in their daily lives? Math word problems claim to test "real-world" problem-solving, but the scenarios and language they use may be far removed from what many children actually encounter. My current research addresses this by listening to African American children describe the mathematics they naturally use and encounter in their everyday experiences. Rather than assuming we know what constitutes relevant mathematical contexts, this work centers children's own voices and experiences. The goal is to develop assessment approaches that authentically connect to children's lived realities, moving beyond one-size-fits-all assumptions about what "real-world" mathematics looks like and creating more equitable measures that recognize the full range of children's mathematical competence.